Standing in front of the noontime crowd at WXPN’s Free at Noon concert on this St. Patrick’s Day, John Byrne sounded almost giddy. “How are ye all?” he called to the crowd as he and his eponymous band launched into their version of the Dubliners’ “The Twang Man,” the story of a man who kills his lover’s new partner, then rolled right into “The Well Below the Valley,” an ancient tale of incest and infanticide, with Byrne’s bodhran leading the driving beat.

If you’re looking for “The Unicorn Song” or “Celtic Symphony,” (or, God forbid, anything tura lura lura) John Byrne is not your man. And he’s not even sure he’s your man for all that much from the Irish songbook. “There’s lots of great people I would hire over me to do something like that,” the Dublin born singer-songwriter says over some avocado toast and egg at Mt. Airy’s Caribbean themed Cherish Philly—the cafe with “barbershop vibes.”

“Oh I think we do it well,” Bryne says of the band’s select playlist of Irish music (they put out a Celtic CD, “Celtic Folk” in 2012 which opened up the Irish Festival route to them several years ago.) But most of the tracks on their three other CDs fall into the “singer-songwriter” and “folk” genres and most if not all of them are written by Byrne himself.

“I don’t know how to shake it anymore. We don’t get a ton of Irish festivals because the band isn’t really Irish either. But I still get that I’m an Irish singer.”

It’s not that he’s complaining. Not really. Byrne is aware that his Irishness is a selling point. The Paddy’s Day XPN Free at Noon concert likely came their way because he IS Irish, born into a working class family in north Dublin, though he’s been a Philadelphian for more than 20 years. (It doesn’t hurt that Philly’s premier public radio station has been his biggest fan from the get-go.) Having an Irish lead singer probably contributed to band opening for a host of headliner Irish bands, including the Saw Doctors, The Young Dubliners, Gaelic Storm, Lunasa, Dervish, Luka Bloom, Hothouse Flowers, and trad superstars Finbar Furey and Sharon Shannon. “And if you look at our albums, Irish influences everything on there,” he points out.

And he’s certainly taken advantage himself of his accident of birthplace to get the band gigs. They do an enormously popular show featuring the music of The Pogues, but he admits that he’s considered adopting a different band name just for those performances.

“I feel a responsibility to the band to get paying gigs for them,” says Byrne, “I have had incredible luck with the musicians around me. Sometimes I look around me on the stage and I can’t believe how lucky I am.”

The group’s one constant besides Byrne himself has been fiddler/cellist Maura Dwyer who has been with the band since its inception. Long-time collaborator Andy Keenan, who produced “A Shiver in the Sky” at Spice House Studios in Fishtown, took a brief hiatus to move to Nashville and tour with Amos Lee but is back with the band. Sharing the stage now are drummer Freddy Berman, guitarist Mike Taylor, and most recently, accordionist Rob Curto.

Byrne concedes he’s probably never going to escape “the Irish guy” niche, but acknowledges that there’s some consolation. Since the band’s first of many sold-out World Café Live appearances, the people who come in for the Irish music leave smitten with what Byrne thinks he and his band do best—original music, his original music.

For example, the band’s last effort pre-pandemic, the critically acclaimed “A Shiver in the Sky,” hit number one on the Roots Music Reports Alternative Folk Charts not long after it was released. The 10 tracks explore the aftermath of trauma and loss—given what was to come in 2019, somewhat prescient—and how each weathered storm passes, becoming just a remnant of itself, “a shiver in the sky.” It never goes away, it changes you, but ultimately doesn’t keep you from moving forward. It’s an acknowledgment of the human condition and a paean to hope.

Byrne’s songwriting chops have not gone unnoticed. Reviewers have actually admitted his lyrics made them cry. One described him as “Bob Dylan meets Luka Bloom,” a thrill for Byrne for whom Dylan is a songwriting inspiration. Just recently, Byrne was invited to participate in Philly Songwriters in the Round, a Nashville-style showcase of songwriters from a variety of genres who perform their own work and talk about its genesis. The mini-concert takes place Thursday, April 6, at The Royal, 1 South Easton Road, Glenside.

Byrne is a rarity among professional musicians in that those without private planes and live-in staff—he has neither—can’t get by without day jobs. Byrne has managed to be a fulltime musician, except for a once weekly stint bartending and Quizzo hosting at Kelliann’s Bar and Grill in Fairmount, for more than a decade. He credits the band’s fans—with gratitude.

“It’s the 1000 fans theory,” he says, referring to the “1000 true fans” concept developed by Wired co-founder Kevin Kelly . “If you have 1,000 fans who are willing to spend $50 to $100 on your CDs, concerts, and merchandise every year, you can make a living as a musician.”

Byrne’s last non-music job was teaching English at The Lincoln Center for Family and Youth, an alternative school for teens other schools couldn’t handle, in Montgomery County.

The music business is tough, but teaching was even more challenging. “That’s the hardest I’d ever worked, the most I’ve ever failed,” he said of his years at Lincoln. “ I thought I was tough. I grew up in North Dublin. But I couldn’t control a class that first year, until I caught their rhythm a little more. Then it was great. Today, I’m still close to some of my students.”

In fact, he credits them for his growth as a writer. “Because of them, I became a better writer,” he says. “Seeing a world I didn’t know existed, rather KNEW existed but couldn’t describe, made me a better writer and an infinitely better person, a more empathetic person. Empathy is something you do have to learn, to work on, and you can’t write a good song without empathy.”

Song writing—any writing—that’s substantive “comes with learning more about life. It’s about getting out of your own little circle,” says Byrne, warming to his favorite subject. “That’s why I love going out on the road. I remember playing in Grand Island, Nebraska, a cool little blue pocket in a red state, then playing down the road in Lincoln for a whole different type of person. You learn what moves them and why they have fears. It comes from something. They’re not idiots. They’re in the best place to see their world and I can’t come in and say, ‘It’s okay to put your guns away.’ It’s not my world. All in all it’s about making that connection with people who see the world differently than you do.”

In his songs, Byrne has never shied away from a controversial subject, whether it’s addiction, bigotry, immigration, or LBGTQ issues. He’s not afraid to go full bore autobiographical either, however personal and painful. “The Immigrant and the Orphan,” the third release by the John Byrne Band, was born during a time when he and his wife Dorothy were dealing with pregnancy loss and infertility and Byrne’s father was facing serious health problems. The elder Byrne (also named John) was himself a singer and musician who opened his home regularly to friends and family for informal sing-songs. The two recorded a folk music collection in 2018—”John J. Byrne and the Twangmen”–which is now in Ireland’ National Folk Music Archives.

One of the songs Byrne identifies as a favorite is “Sing on Johnny,” which dealt with his own fears about his father’s illness. “Sing on, Johnny there’s a war ahead, sing on Johnny, there’s a battle ahead, when the wind blows ill just take a deep breath. Sing on Johnny in the salty wind, ‘cause you can’t get to heaven in a sinking ship.”

Of course, there are limits to plumbing one’s own life for lyrics. After his father died, Byrne wrote a song “that even I thought was too sad.” He sent it to his brother, Damien, also a musician. “He said ‘It’s beautiful and I never want to hear it again.’”

Along with entertaining fans on Facebook Live during the height of the pandemic—the only “venue” available at the time–Byrne also turned his hand to writing a screenplay based on his song, “4th and Diamond,” about a man who encounters an ex and thinks the old fire is rekindling—until she asks for money. He’s now at work on a “mockumentary.”

And since “Shiver” was released, Byrne has written enough songs to go back into the studio with the band and start recording, with Andy Keenan on board to produce. He’s already produced some demos and is toying with the idea of mixing his original songs with some favorite folk tunes like Cliffs of Dooneen, an Irish ballad made famous by Planxty, and Fiddlers’ Green, recorded by The Dubliners. “Or at least recording them to have them, maybe to release them as a collection,” he says.

Once all the details are worked out, he may turn to crowd-sourcing to finish the product. “I don’t want to go to Kickstarter until the record is close to being made,” he says. “I want people to know that it’s going to be made, that they’re really just ordering early.”

Long ago, Byrne abandoned the idea of chasing a recording contract. “We did that when I was with Patrick’s Head [his previous Irish band]. It was ‘we’ll record that song that will get us a deal,’ and ‘we’ll put out that album which will get us a deal’ and it just never happened. I’m not chasing anything anymore except trying to make it good. I just want to play and think ‘that was good.’”

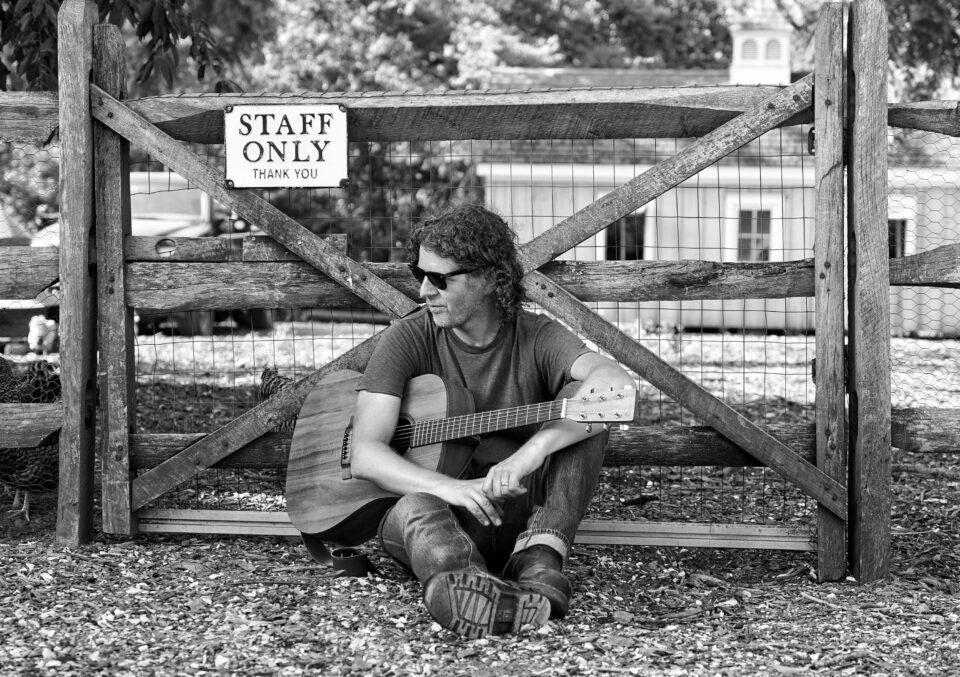

Photo by Suzanne Kulperger