Forward: Edna O’Brien, my favorite Irish woman writer, often referred to as the “Queen of Irish writers,” died Saturday on my birthday. I’ve always felt a kinship with her and particularly loved her short stories. It seems unfair that she never won the Nobel Prize in Literature or the prestigious $40,000 Booker Prize that is often seen as a precursor to the Nobel.

She was honored with the title “Saoi,” meaning “wise one,” the highest honor bestowed by Aosdána, an association of Irish creative artists in 2015 and awarded the biennial David Cohen Prize in 2019. France made her a Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2021.

Her many accolades include Irish Pen Lifetime Achievement Award, the American National Art’s Gold Medal, the Ulysses Medal, the PEN/Nabokov Prize, and the Frank O’Connor Award for her story collection “Saints and Sinners” and several years ago, a Lifetime Achievement Prize in London for having “moved mountains both politically and lyrically through her writing.”

And move mountains she did.

(This July 1997 interview is included in the collection Irish Literary Portals)

Irish expatriate writer Edna O’Brien, whose home base has been London for the past 30 years, has long been one of my favorite writers. Her themes mostly centered on women have been about love, loss and relationships. Her style, effortless, lyrical, comic and naughty. For an Irish writer in the 1960s, her subject matter was daring and experimental.

Her 1960 debut novel, “The Country Girl,” provoked controversy in conservative Catholic Ireland and was banned by the local archbishop and publicly burned by the local parish priest.

Recently we met. There is a diaphanous almost ethereal quality about her. The look of a porcelain doll with a gypsy soul. A woman who has loved hard, and lived hard with some regrets. A passionate woman, tough, sensitive and fragile.

Striking in appearance—white, white face, hennaed hair, burgundy lips, smoky blue eyes—wells of wisdom and sadness in an old soul.

There is a sense of someone who has been sustained by and made sacrifices for her writing perhaps more than she expected. There is an unmistakable look of vulnerability—of a woman not totally sure of herself despite all her successes.

We talked about many things—her writing, raising two young sons alone, abortion, the politics of Northern Ireland, and her most recent book, “Down by the River,” a horrific yet exquisitely told tale of a 14-year-old Irish girl who is raped and impregnated by her father.

S.C.: This is a powerful but disturbing book to read. How did you feel about writing it?

O’Brien: This was a very hard book for me to write. It took me a long time and I did a great amount of research. With a story as perilous as this, I had to see a lot of people. For the most part, people were helpful. However, each one wanted me to emphasize their point of view. But a novel is not a tract; it’s a piece of fiction.

S.C.: What is the current law on abortion in Ireland?

O’Brien: It still is illegal. Somebody said, “We don’t have abortion in Ireland, we export it.” That’s a pretty accurate assessment, I think. There has been no legal change or judicial change as yet but there has been, I think, a lot of change in the country itself and in the psyche. Because up to that time, even the mention of the word was taboo. Now it is more open.

S.C.: What are your personal feelings about abortion?

O’Brien: I feel that to have an abortion is a huge, traumatic and personally wounding thing—to any woman or young girl. It is not something that someone recommends, like having a gin and tonic or going out to dinner. It’s a very big thing and I would feel only empathy or compassion for someone who feels she has to. The opposite group is very vociferous. They are saying you must not. I don’t say you must not have an abortion but if you have one, I’m not going to punish or criminalize you.

S.C.: Because this story of rape and incest is set in Ireland, a strictly Catholic country with a strict moral code, it seems particularly more shocking and horrifying.

O’Brien: I suppose it is more poignant in an extremely devout and notably Catholic country. The Irish people have a strong disposition towards guilt—I have it myself. Therefore, the fear and concealment is even greater—for both the perpetrator and the girl. In my book the girl says, “The person who it is, is the last person it should be. I would rather not say, I will not say ever.”

S.C.: What were you trying to achieve with this novel?

O’Brien: I was trying to write about a theme that is very fundamental and, although utterly secretive, is true in every community all over the world. People have asked, “Is this your story?” I think or I hope I have more class. I wouldn’t even answer that question—do you know what I mean?

S.C.: The language in this book seems like somewhat of a departure for you.

O’Brien: Well, I think every book for every writer worth his or her salt has to be a departure. Because every book is a rehearsal. Unconsciously, you have to be bolder and more experimental—without being untruthful.

S.C.: Who are your favorite writers?

O’Brien: I love Joyce and I love Faulkner. They are the two kings. They are bread and wine for me and you know what that turns into with a bit of blessing! When Faulkner won the Nobel Prize, he said a wonderful thing. He said, “There is really in the end, only one subject a writer should engage in—the human heart in conflict with itself and others.”

In “Down by the River,” there are a multitude of conflicts—the conflict of having to hide the secrecy of having to run away, the conflict within the community, the conflict within the country of people taking different sides, the conflict of people not believing or not wanting to believe, the conflict of the father, who until the very end thinks he can elude it and yet, when his number is up—his own conflict when he takes his own life. It is layer upon layer of conflicts which seems to me to be vital to a piece of fiction.

Light fiction is rather tepid and un-dangerous. Maybe because I am a wild Irish woman, I think fiction should be dangerous. By dangerous, I don’t mean sensational.

S.C.: You seem as if you have made huge personal sacrifices for your writing.

O’Brien: Absolutely. You have to. I often joke that I need a wife. I say if I were a male writer, I would have some very indulgent and helpful woman. Whereas, a woman writer has to be alone. No man would be an acolyte to me—why should he be!

S.C.: Because of your writing, did you have to give up a lot in your personal life and your relationships?

O’Brien: I think so. I have lived a very secluded life.

S.C.: For how long have you lived a secluded life?

O’Brien: I would think all my life. To write, you have to go into that lonely room of yourself and you have to stay there.

S.C.: That could be painful, I think.

O’Brien: You’re telling me! It can be excruciating!

S.C.: You were married for 15 years. Did you ever want to get married again?

O’Brien: I’ve fallen in love a few times—not many. I would say that if you love someone and live with them, whether or not you actually have the marriage certificate, that’s marriage, Yes, I have longed for that companionship and that reciprocation of love. Of course I have. I’m a very emotional creature.

S.C.: Now that you are very well established, do you want to stop and take time out for yourself and just have fun?

O’Brien (laughing): I doubt it. It’s so funny—last night I was doing a reading in Manhattan and the girl who was running it said, “Edna, have fun.” My answer was “Look, that’s not a word that is featured in my inner vocabulary.” We have to deal with the cards that God gives us. Maybe I will have the things I long for in my personal life but I would still have to write. Writing, to me, is as essential as breathing.

S.C.: Was it difficult bringing up two children alone while trying to write?

O’Brien: Of course, it was hard financially because I was the breadwinner. But what they gave me back in enchantment and love made up for everything. They were little sweethearts and little rogues as well. When I used to lock myself away to write, they would put little notes under my door which said, “We miss you, we are not well or we need you.” Little blackmailers!

S.C.: Now that your sons are grown, where do they live?

O’Brien: Nowhere and everywhere—London, Chelsea, in County Clare, Ireland, which is my birthplace, and in New York where I will be teaching a writing course at NYU (New York University).

S.C.: Have you been following the recent elections in Northern Ireland?

O’Brien: Of course. I wrote a piece in the New York Times this past January. I was trying to tell the world what Unionists are really like—you know what I mean. Oh yes, I feel very strongly about it.

S.C.: Do you think there will be any changes with Tony Blair and the Labour Government?

O’Brien: I hope the Labour Party will bestir themselves. But you see, Northern Ireland is the last ligament of empire for England. The English people feel this possessiveness about it. The 300–year union with Ireland is not a 300-year union, it’s a 300-year conquest. Let’s get the ****** words right!

I feel very passionate about this and would say this to Tony Blair or to anyone. Of course, we have to wait and see. I don’t think there will be major changes. I would like to think there will be. At least Blair won’t have to count on the Ulster Unionists to keep him in office like John Major did.

There is still the notion in the English psyche that these six counties are their property. They were arbitrarily divided in 1922. We’re always hearing the word “democracy.” but democracy was fouled up at the commencement.

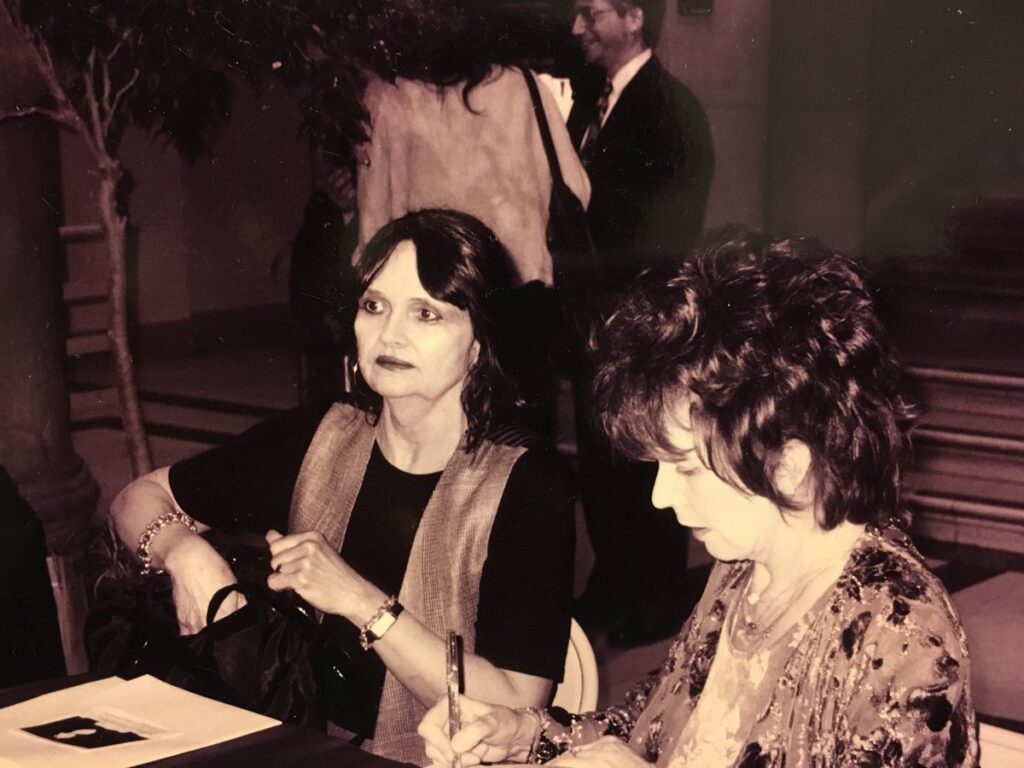

Postscript: A year after this interview, I attended a small private dinner for Edna O’Brien at The Plough and the Stars restaurant in Old City Philadelphia. At one point in the conversation, I said “Edna, you should position Gerry Adams for the Nobel Peace Prize.” There was total silence at the table. No one said a word. The tension was palpable. I turned to my friend W. Speers, The Philadelphia Inquirercolumnist and suggested we go to the bar for a drink. When we returned, everything was back to normal. I realized I had unintentionally struck a chord. This was her party. When she was leaving, she walked up to me and gave me a hug.