Review: “Sara & Gerald …Villa America and After”

By Honoria Murphy Donnelly

With Richard N. Billings

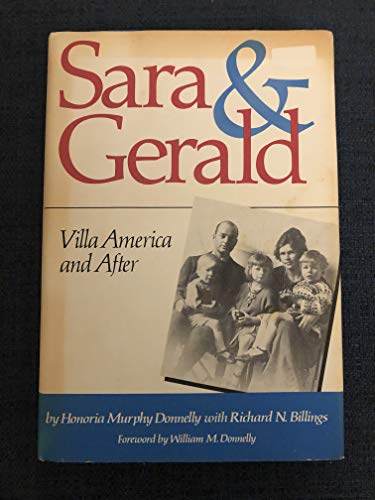

Sara and Gerald Murphy had an uncanny knack for infusing even the quotidian with an artistic flair. These wealthy sophisticated Long Island Brahmins sailed for Europe in 1921 with their three young children disillusioned with what they perceived as the cultural aridity of post-World War I America. Their destination was Paris. They were not famous but they were destined to become famous by association with American artists and writers living in Paris in the 1920s, the Lost Generation.

Although at least a decade older than the artists and writers they befriended – F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso being the more famous among them – the Murphys served as their muses encouraging them, entertaining lavishly and opening their home to them, Villa America a sprawling estate with its jungle-like gardens tumbling down to the sea in Antibes on the French Riviera.

Their generosity extended to discreetly depositing cash when needed in either Hemingway’s or Fitzgerald’s or Picasso’s bank accounts. Their friends became their family.

F. Scott Fitzgerald idolized them. They were his inspiration for Nicole and Dick Diver in “Tender if the Night.”Yet, his characterizations more resembled Scott and his disturbed wife Zelda. Sara Murphy hated the book and rejected any semblance to herself and her husband and anyone they knew.

The Murphys had everything – then tragedy struck and their two teenage boys died within a few years of each other. First, their oldest son Baoth died at 16 from spinal meningitis; then a few years later, their son Patrick died from tuberculosis at 17. Gerald Murphy, a promising artist, stopped painting on the day he learned that Patrick had tuberculosis. When Patrick died on March 17, he never celebrated St. Patrick’s Day again.

Friends of the Murphys’ were in shock and rallied around them – and this is where we are privy to some very profound letters of condolence from friends who grappled with their own grief and their inability to comprehend how fate could deal such a cruel blow twice to the undeserving Murphys.

Gerald and Sara Murphy were revered for their courage through great adversity. In a letter to the humorist Robert Benchley, her close friend, the writer Dorothy Parker said, “I’ve been putting off talking about the Murphys til now, because truly Mr. Benchley, it would break your heart. And why in the hell did this have to happen to them, of all people.”

The letter the Murphys cherished the most when Patrick died was the letter from Scott Fitzgerald: “The telegram came today… it is hard to say which of the two blows was conceived with more malice… Fate can’t have any more arrows in its quiver for you. The golden bowl is broken indeed and it was golden; nothing can ever take those boys from you now.”

In letters to their friends, the Murphys did not share their full feeling about their tragedy, but they were very candid about their feelings with Scott Fitzgerald.

After the death of Patrick, Sara wrote: “Of all our friends it seems that you alone knew how we felt these days. You are the only person who we can tell the bleak truth of what I feel. I don’t think the world is a very nice place”

All that was left for the Murphys now was their daughter Honoria, named after Gerald’s grandmother who emigrated from Ireland – a fact Gerald Murphy never shared with Honoria since he chose not to accentuate his Irish heritage, preferring the company of Anglo-Saxon Protestants to Irish Catholics.

Honoria realized her parents’ dependence on her and stayed close to them for the rest of their lives and it is through her diary and meticulous record keeping that we have this important historical record.

It is through Honoria’s sensitivity and insight into her parents’ relationship that we are able to experience the rhythm of the Murphys’ daily lives and their relationships with their friends. Their story would not have been preserved without her keen powers of observation and the lively, intimate diary she kept, which is interspersed throughout the book.

The Murphys’ personal history intertwines with the private lives of Fitzgerald and Hemingway and so many others in Paris at that time. The correspondence alone – the lost art of letter writing – makes this book worth reading, and the Murphys and their friends were prolific letter writers.

In his book “A Moveable Feast,” an account of his Paris years written when he was ill and depressed, Hemingway wrote with the Murphys in mind: “The rich never did anything for their own ends. They collected people as some collect pictures and others breed horses. It was only their fault for coming into other people’s lives. They were bad luck for people but they were worse luck for themselves and they have lived to have all of their bad luck finally; to the very worst and that all bad luck could go.”

Upon reading Hemingway’s words, Gerald Murphy revealed his reaction in a letter to his closest friend, the poet Archibald MacLeish: “What a strange kind of bitterness—or rather accusitoriness. Aren’t the rich (whoever they are) rather poor prey? What shocking ethics! How well written, of course!”

Editor’s Note: The Sara and Gerald Murphy papers are housed at Yale University.